Aggregate Production:

Stories of old Texas often tell of travelers mired deep in mud, stranded in rainstorms that washed through unpaved streets and roads, leaving produce, livestock, mail, and passengers well short of their destination. Frustrated, the Texas Farmer’s Congress pushed for state control of roads in 1902, and the Texas Democratic Party followed suit by including a state roads network in its political platform. A lobbying group, the Texas Good Roads Association, was established in 1903 to further press the cause. Government began to respond: in 1905, the State Legislature created the Office of Public Roads, and Congress’ passage of the Federal Aid Road Act led to the Texas Highway Department in 1917.

These private, state and federal moves were the start of a major, multi-decade campaign in Texas to build roads – including many hard-surface, multi-lane, high-speed routes – throughout the state. With these new roads, the convenience, ease, safety, and commercial benefits of travel have boomed in Texas.

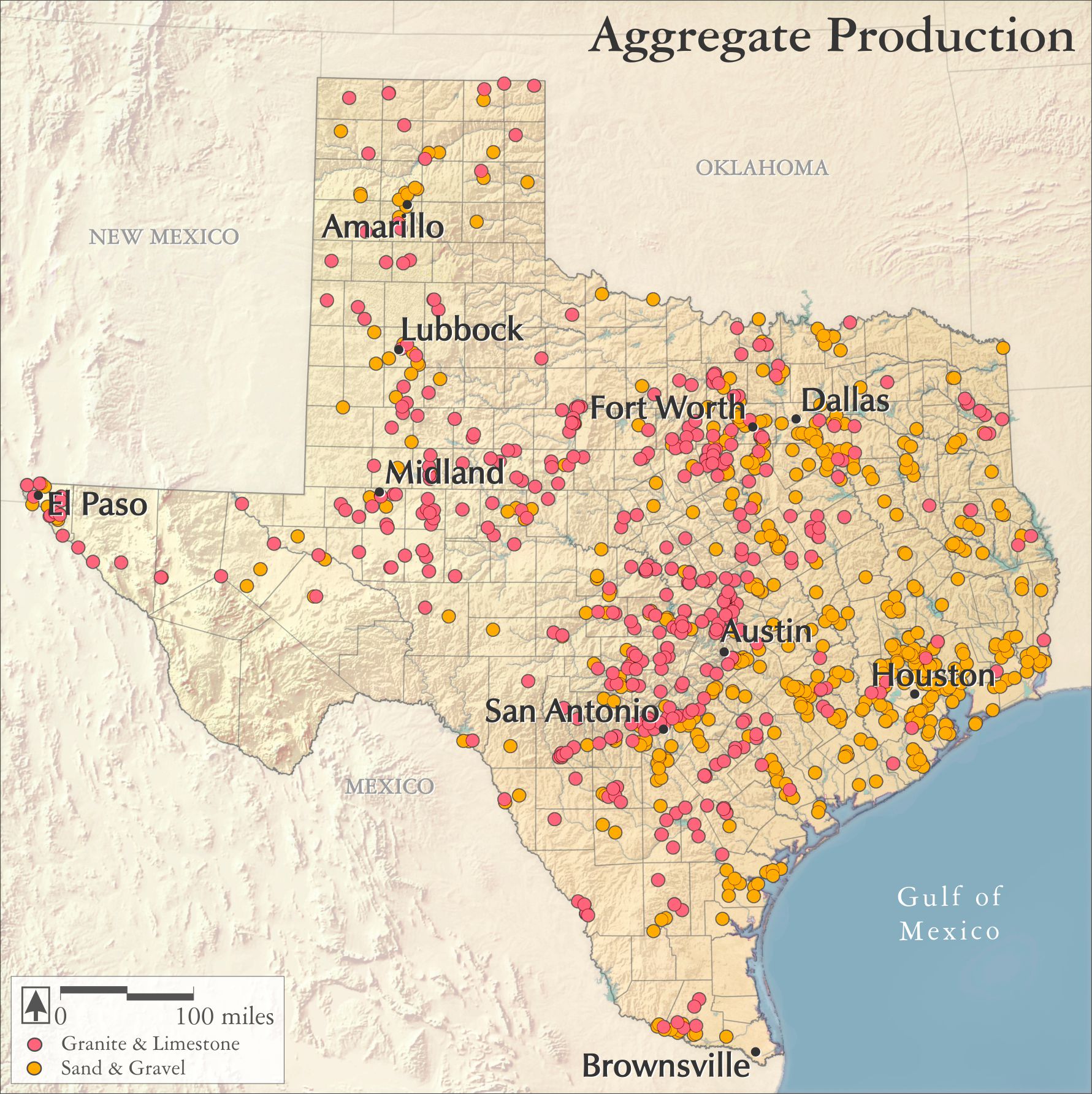

However, as the network of roads (Texas state and federal routes tally over 80,000 miles in length!), parking lots, airstrips, and other hard surfaces has grown, the downside of this paving boom has become more evident (Legislative Budget Board 2014, p. 489). One problem has certainly been the state’s many aggregate strip mines that supplied the required sand, gravel, and stone. To help you picture this impact, this map shows over 1140 active and expired aggregate strip mines in Texas (some over 2000 acres in size, and as deep as 275 feet) (TCEQ 2017; TXDOT 2009).

These quarries can cause a variety of serious environmental problems, including the loss of farmland, and flood runoff and non-point source pollution from broken dikes. Unfortunately, there is not as much effort to mitigate those impacts as might be hoped. In 1975, the Texas Legislature chose not to require reclamation after mining aggregates, unlike most of its sister states (Interstate Mining Compact Commission 2013; TAC § 342; Lowerre 2017; Tex. S.B. 66, 64th Leg., R.S.). As a result, the strip-mined land, including its vegetation, soil, and general topography, has been damaged and slow to restore to a productive level.

Sources:

An Act Relating to the Control and Regulation of Exploration for and Surface Mining of Minerals. Tex. S.B. 66, 64th Leg., R.S. (1975).

An Act Relating to the Regulation of Certain Aggregate Production Operations. Texas H.B. 571, 82nd Leg., R.S. (2011).

Herrington, Chris. 2017. Manager, Water Resource Evaluation Section, Watershed Protection Division, City of Austin. Personal communication, 31 January 2017.

Interstate Mining Compact Commission. 2013. IMCC Noncoal Minerals Questionnaire.

Legislative Budget Board. 2014. Fiscal Size-Up: 2014-15 Biennium. Legislative Budget Board. Austin, Texas.

Lowerre, Rick. 2017. Attorney. Personal communication, 23 January 2017.

Regulation of Certain Aggregate Production Operations. Texas Administrative Code, Title 30, Part 1, Chapter 342.

Texas Aggregate Quarry and Pit Safety Act. Natural Resources Code, Section 133. Acts 1991, 72nd Leg., ch. 668, Sec. 1, Effective August 26, 1991.

Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. 2017. Water Quality General Permits & Registration Search – Advanced. http://www2.tceq.texas.gov/wq_dpa/index.cfm. Accessed January 25, 2017.

Texas Department of Transportation. 2009. Pit_Quarry_Inventory_file. December 7, 2009.