Road Kill

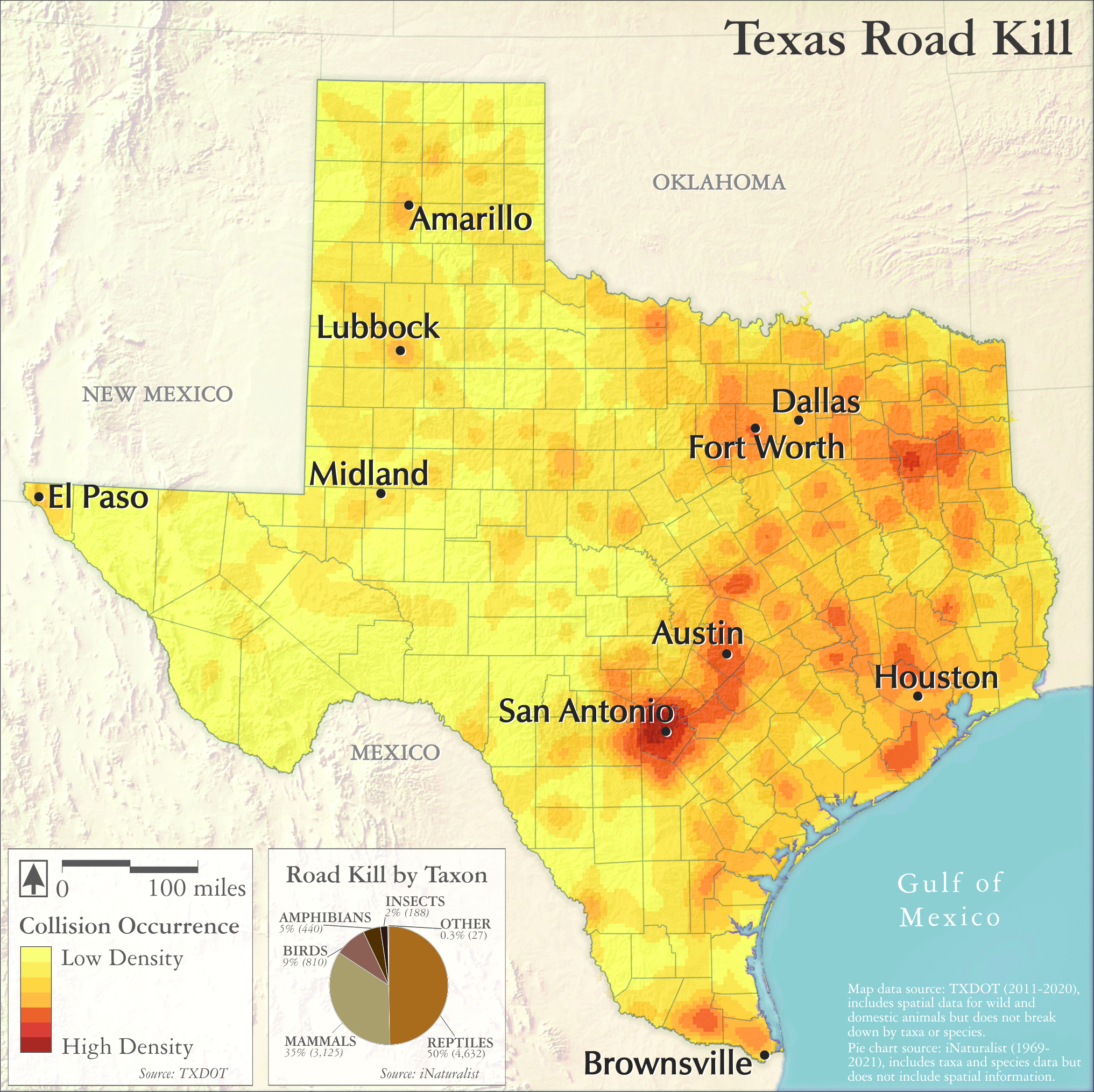

Here is a map showing the pattern of more than 103,000 collisions with animals, both domestic and wild, on our state’s roads, reported from 2011-20. These reflect only the more serious, reported crashes (in fact, these accidents were associated with 270 deaths and nearly 2100 incidents where serious injuries were suspected).

These Texas Department of Transportation data do not break out the kind of animal involved beyond whether the poor creature was domestic (32,438) or wild (71,007). However, a project organized on iNaturalist in 2018 by Dr. Christopher Schalk at Stephen F. Austin State University, with participation from over 690 citizen scientists gives a more clear idea of the carnage.

This iNaturalist data, covering more than 9300 animals, shows that the butchery extends to over 500 species. Half of the reported corpses are reptiles, 35% are mammals, 9% are birds, and 5% amphibian. The most typical victims are sadly familiar to many of us: the common raccoon, nine-banded armadillo, Western diamond-backed rattlesnake, striped skunk, and Virginia opossum. Some though are alarmingly rare, including the endangered ocelot, of which seven were found dead on Texas roads in 2016 alone.

Aside from the obvious gore of the body count, the map points to several underlying stories – the giant number of vehicles zipping across the state (22 million, as of 2021), the enormous network of roads in Texas (over 315,000 miles’ worth, as of 2019), the extensive fragmentation of native habitat as the state is increasingly criss-crossed by pavement, and the potential for crowd-sourced science to push for good solutions.

Fortunately, the Texas Department of Transportation is starting to find some promising ways to lowering risks for these collisions and the associated bloodshed. One encouraging example is on SH 100, the road between Brownsville and South Padre Island, where five culverts now allow wildlife to pass peacefully from one side of the highway to the other. In fact, game cameras captured more than 1700 animals safely using just one passageway during a recent 18-month period!

And one last heartening part of this story – there is some evidence that the road kills are providing fodder for our hungry black vulture and crested caracara friends.

Selected Sources:

iNaturalist. 2021. Roadkills of Texas. https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/roadkills-of-texas

Loftus-Otway, Lisa. 2019. Incorporation of Wildlife Crossings into TXDOT’s Projects and Operations. Report No. FHWA/TX-19/0-6971-1. University of Texas at Austin, Center for Transportation Research.

Meiburg, Jonathan. 2021. A Most Remarkable Creature: The Hidden Life and Epic Journey of the World’s Smartest Birds of Prey. Knopf. New York.

Miller, Matthew. 2016. “A Shocking Surge of Ocelot Deaths in Texas.” Cool Green Science.

Roe, Russell. 2018. “How Did the Wildlife Cross the Road?” Texas Parks & Wildlife. October 2018.

Schalk, Chris. 2021. Assistant Professor, Temple College of Forestry and Agriculture, Stephen F. Austin State University. Personal communication. 2021.

Texas Department of Transportation. 2021. Crash Records Information System. https://cris.dot.state.tx.us/public/Query/app/welcome

Weisman, Dale. 2021. “Crossing to Safety: How Driver Attention and Innovative Design can help protect Wildlife.” Texas Highways. January 7, 2021.

Wilkins, Devin, Kara Kockelman, Nan Jiang. 2019. “Animal-Vehicle Collisions in Texas: How to Protect Travelers and Animals on Roadways.” Accident Analysis & Prevention. Vol. 131, pp. 157-170.